When I have spare time, I enjoy reading books from a wide range of topics, and every so often there’s a “meta” book I read about the act of learning itself or personal development in general.

Recently, I finished reading a book called, “Ultralearning: Master Hard Skills, Outsmart the Competition, and Accelerate Your Career” by Scott H. Young. The main thesis of the book is that anyone is capable of learning pretty much anything, and gives a set of guidelines for learning a ton of information in a short amount of time.

The book goes further than just learning conventionally. The stories and methods it discusses are specific to self-directed learning, also known as auto-didacticism. Young gives examples of autodidacts such as Eric Barone, who taught himself how to draw, make music, write code, and more to create his dream video game, Stardew Valley. The farming simulation RPG was, and still is, very popular across multiple consoles and had sold over 10 million copies, as of January 2020.

Young writes about famous geniuses and dissects their learning styles and tries to shape the narrative that yes, there are certain people who are naturally amazing at certain things and learn certain subjects quite easily, but for the most part, many of the people whom we consider “genius” are just very dedicated and passionate about what they learn.

Cognitively Situated

One of the main topics of Ultralearning is the concept of directness. Young defines directness as simply applying the skills you learn directly to the way you want to use them. For example, if you want to learn how to write code, simply watching videos and going through tutorials will only help to a point. If you’re goal of learning to write code is to make a website, the best way to learn is by, you guessed it, making websites.

The concept of directness may sound like common sense. Sure, if I want to get good at running, I simply need to run more. Practice makes perfect, 10,000 hours, and all that. But I think directness in this context goes further than “practice makes perfect.”

Directness as a concept is seen in other subjects as well, such as neuroscience and philosophy.

![Sketch of the embodied cognition perspective [11]](https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Pierre_Levy6/publication/295399680/figure/fig2/AS:331556657877000@1456060675426/Sketch-of-the-embodied-cognition-perspective-11.png)

In neuroscience, there is the theory of situated cognition. As explained in the International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, situated cognition is defined as:

“… a range of theoretical positions that are united by the assumption that cognition is inherently tied to the social and cultural contexts in which it occurs.”

We find situated cognition validated in the real world through human interaction with activity, context, and culture. After all, we are a combination of nature and nurture when we are growing up, a metaphor for the metaphor, “you are what you eat.”

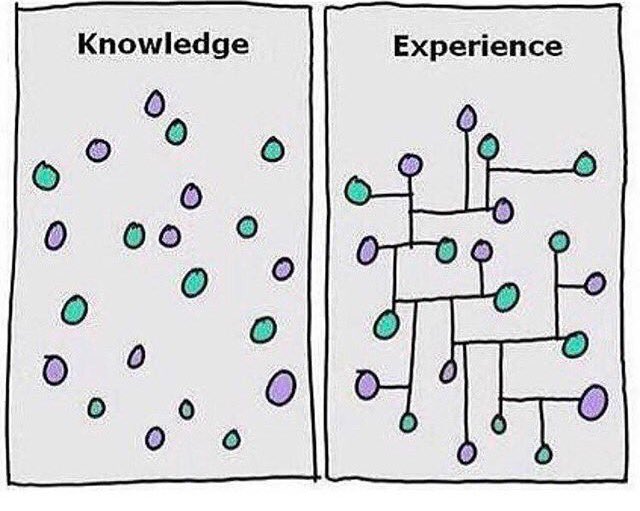

Texts about this theory go on to explain that the things we know or get good at are connected with our application in our immediate physical world. Learning anything, from a new language to a physical skill is seen not as a silo out in its own world, but is actually very contextual.

When we learn something, having context to apply our knowledge is one of the most important considerations. Thinking about why you want to learn something and the end goal you are trying to reach will not only make learning more meaningful, but you can make sure along the way that what you are learning is worthwhile to achieve your goal.

The nature of learning requires newly acquired knowledge to be actually used to really make what we learn stick. Humans are social beings, and the way which we give meaning to what we know is by having experiences and engagements with the world.

This is also why learning communities are so successful, for example, when looking at online courses, many of them have associated Slack channels or Discord servers filled with both current and former students to converse with. Even going back a bit further, to plain old forums, people having meaningful conversation about a subject can truly get more of out it. I guess participation points aren’t for nothing!

Let’s be Pragmatic about it

There is also the philosophical tradition known as pragmatism. Charles Sanders Peirce, one of the “classical pragmatists”, first defined and defended the view in the United States around 1870.

“The core of pragmatism as Peirce originally conceived it was the Pragmatic Maxim, a rule for clarifying the meaning of hypotheses by tracing their ‘practical consequences’ – their implications for experience in specific situations.”

Pragmatism says that meaning is found when something we know in theory is successful in practice. Pragmatists prioritize understanding things in terms of concrete tasks and activities rather than in terms of abstract theory. Pragmatists go so far to say that words don’t have inherent meanings attached to them from birth — instead, they gain their meanings through repeated use. At a basic level, I like to think of Pragmatism as “the philosophy of action.”

We can relate this definition to learning about something as simple as an apple, when we’re babies or toddlers. The word “apple” doesn’t mean anything to a baby, but when the baby sees or eats an apple and associates the word with the fruit, the baby assigns meaning to it and recognizes what an “apple” is in a real context.

You can read and watch all you want, but when you get right down to it, nothing will make you believe in something more than seeing it work in the real world. I’ve read a lot of self-help books over the years, and from all the things each book will have you take away, the things I remember most are the concepts I’ve tried and seen work in actual situations.

It’s kind of like your friend assuring you that “this too, shall pass” when something negative happens in your life. It’s easy to give advice when you’re not in a situation or haven’t experienced it yourself. Even with a concept as simple as giving advice to someone, you can see that we always trust the words of someone who went through what you are currently going through leagues ahead of the advice from a well-meaning friend.

After everything is said and done, we might see that our well-meaning friend was correct, just as was the person who had gone through the experience themself. We still would assign more value to the advice of an experienced person over someone else.

In Closing

If you’re interested in the concept of learning, I would highly recommend reading Ultralearning, as it tells great stories, gives concrete examples, and is all-around an interesting read. When you hear that someone has studied the entire MIT undergraduate computer science curriculum in months rather than years, as Young did, it sounds ridiculous. When you hear it right from someone who did it, it sounds possible.

Even though Young learned all that information in a short amount of time, what he still remembers years later is a much smaller amount of the content he consumed. Nobody would be expected to remember an entire degree’s worth of information forever, but not surprisingly, the things he does remember are the concepts and skills he used regularly afterwards.

Applying your learnings to the real world isn’t just better for memory, it’s also more rewarding. The satisfaction of finishing a painting in real life is much more rewarding than finishing watching a YouTube series on painting.

I want to make sure that I don’t come across as someone who is saying that passively learning things isn’t valuable, because it is. The proof is in the pudding, though, as I’m sure you’ve experienced yourself. The things we do regularly or even practice every so often, sit much more comfortably in our minds than the things we learn once, and store away in the attic to forget about.