When I was in middle school, I first learned about the scientific method. I was told there exists a process that scientists follow to make discoveries, and was amazed that I could follow the same process that impactful scientists follow in my own classroom.

We spent many lessons conducting experiments and following this process, asking questions, and testing our theories. I was never great at science in an academic sense, nonetheless I always found it interesting and recognized its importance.

From Design to Science and back again

At its core, the scientific method is a problem-solving framework. The steps are as follows:

- Make an observation

- Ask a question

- Form a hypothesis, or testable explanation

- Make a prediction based on the hypothesis

- Test the prediction

- Iterate

If you’re a design practitioner or in the tech industry, this process may sound familiar to you, and not just because it’s the scientific method that many of us learn in school.

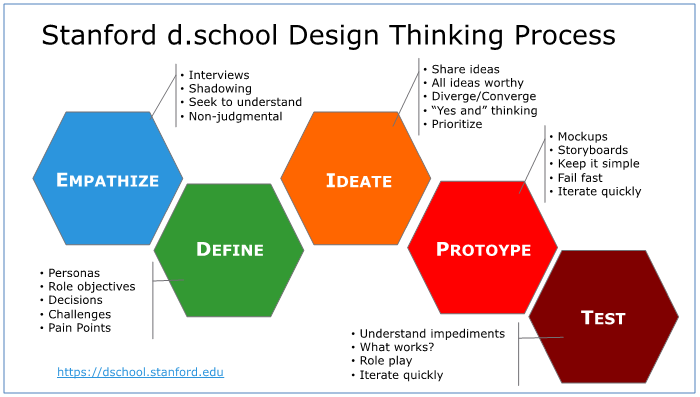

Design-thinking has become a buzzphrase, but has existed in some form for as long as people have been developing products, though it’s been popularized in the last 15 years or so.

The design-thinking framework is as follows:

- Frame a Question

- Gather Inspiration

- Generate Ideas

- Make Ideas Tangible

- Test to Learn

- Share the Story

Lather, rinse, iterate

The main similarities of both lie in the larger idea: testing and iteration. One of the most important aspects of both science and design is to test your ideas in real-world scenarios and iterate as necessary.

Iteration in this context is not repetition, we’re not embodying the old saying, “…doing the same thing over and over again, but expecting different results.” Iteration differs from repetition because when we iterate, we slightly alter what we are testing, not testing the same version over and over again.

Within each iterative step, we test the same version multiple times, but without changing what we test, we’re not getting the best bang for our buck with each round of testing.

No idea is going to be perfect the first time around, so its up to us as developers of ideas and problem solvers to continually iterate and tweak our solution until it’s the best it can be in the given scenario.

When it’s more trouble than it’s worth

Something important to remember is there comes a point of diminishing returns. This applies more-so to product development than scientific work, because developing software doesn’t usually come with the responsibility of something like a life-saving drug.

We can observe diminishing returns when we enjoy a freshly baked chocolate chip cookie. The first cookie is heavenly, so we decide to have another. The second cookie is also delicious, but not quite as enjoyable as the first. If we continue down this path of cookie inhalation, after four or five (to each their own), we probably won’t enjoy them at all anymore.

We can iterate twenty times on something and it might be better than it was the fifteenth time, but after going through the process enough, we can gauge when is truly the balanced time to call it quits.

There’s no hard and fast rule around iteration in software because every situation at each company is different. At some companies, they may find that the sweet spot for them is testing and iterating three or four times before delivering, while others may take eight to ten iterations.

With software (and possibly science, but I wouldn’t know for sure since I’m not a scientist), we have deadlines to hit. We can’t spend the rest of our days iterating on a feature or product until it’s perfect, which is an illusion anyway.

We can iterate and test a handful of times before we have to deliver tangible value to our customers and the business, so it’s important we test the right way, just enough, before iterating again.

Companies tend to follow the Agile methodology, so they have a framework to follow where they can consistently deliver value to the business and the customers over time.

In the days of yore, the de-facto way to build product was using the Waterfall methodology, in contrast to Agile, where teams deliver value in one big release after months or even years of development.

Testing can be hard to do, which is why so many companies simply don’t do it at all. It takes time and upfront effort, and when companies equate value with production, it can be a hard sell to continually do it. There’s been a ton of writing around how to conduct lean user research, so I won’t write about it here.

Our work is never done

Both science and design are “never finished”. Have you ever used a successful piece of software that never has updates? Or seen a news article that reads something like “Coffee is good for you” a year after reading an article titled “Coffee is bad for you”?

That’s kind of the point, though isn’t it? Scientific studies are happening all the time and they’re always proving and disproving hypotheses.

Nothing is certain 100% of the time, especially when dealing with something as erratic as human behavior. As outlined earlier, science usually has more weight to it’s decisions that software, so we don’t need to think that an immutable scientific truth such as gravity can be disproven as easily as a pattern in a social media application.

I like to push the importance of “done over perfect” in my job, but of course there’s a lot of nuance in that phrase. There’s a balance that we are all striving for, while trying to destroy the perfectionist in ourselves. We want the things we deliver to be great without being reckless in our delivery or overthinking ourselves into a rut.