“A candle loses nothing by lighting another candle”

James Keller

For whatever reason, many times in my life I’ve had a bad case of “Keeping up with the Joneses.” Call it growing up in white suburbia, being a neurotic millennial, or living in the digital age of vanity metrics, but there’s always been someone to compare myself to who’s got it all figured out. On a logical level, I understand that I can’t compare myself to anyone but me, who I was yesterday in contrast with who I want to become tomorrow. However, on an emotional level, it’s a bit of a different story.

Tell me if the following sounds familiar: You’ve finished work for the day and have a to-do list of your own planned for some personal projects you’d like to make regular progress on. Maybe you want to become better at drawing, so you’ve decided to crack open an Andrew Loomis book and start having fun. Before doing so, you decide to hop on Instagram or Twitter to relive your FOMO, and start scrolling.

Before long, you see that someone has posted a photo of their new painting and is getting rave reviews in the comments. It looks phenomenal, the brushstrokes, lighting, and values are all just right. You start to feel nervous, imagining what it would take for you to get to that level. You’re not ready to post your artwork online, you feel like you’ll never be that good! You feel behind in the drawing world because in your view, someone in your greater network making progress on their own somehow means you’ve made less progress.

If the above situation sounds slightly silly, it’s supposed to. It doesn’t seem silly when we’re in the middle of such an experience, but when we talk about it to ourselves or others later, it sounds almost ridiculous. This is the danger of unnecessary comparison and zero-sum thinking (plus some perfectionism peppered in).

Most things in life do not have a health bar hovering above them, depleting each time someone does something that you don’t. Just because you publish a new edition of your newsletter, that doesn’t mean I’m one blog post short in the eyes of the public. One can love their children the same amount. Loving more than one child doesn’t mean each child receives less love.

Regardless of privilege, someone is always going to have things “better” than you and someone is always going to have things “worse” than you. It’s all about perspective and what you value, of course, but this old adage does little to ease my mind about comparing myself to others based solely on outward situations. I can’t help but wonder if there’s a better way to think about this.

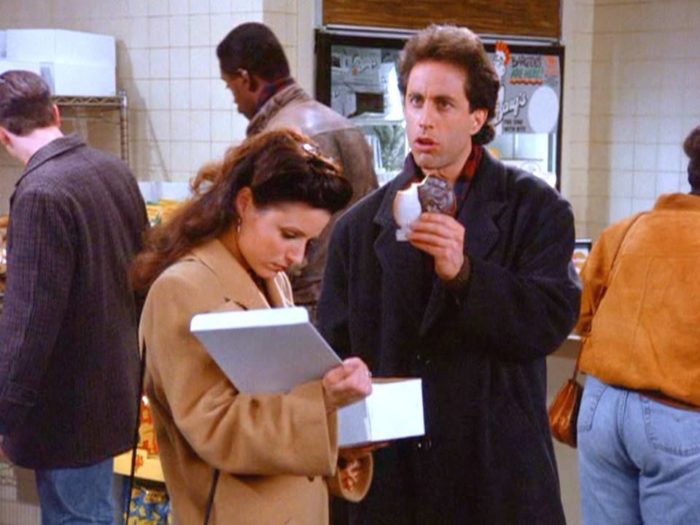

“Look to the cookie”

Zero-sum thinking is typically created by “black and white thinking”, a defense mechanism also known as “all or nothing” thinking or “splitting”, where we tend to think in extremes without a middle ground. Imagine a student, who feels that their only two options are either to get good grades or drop out of school. They fail to see the myriad of other options between the two, namely the “gray area”; we do this to ourselves in the places of our lives where it’s least useful.

In game and economic theory, a zero-sum game is a situation in which each participant’s gain or loss of utility is exactly balanced by the losses or gains of utility of the other participants. Along with the economic situation, this concept goes further to thought. We experience “zero-sum thinking” where we perceive situations as zero-sum games, feeling like someone’s gain is another’s loss. In other words, you gain, I lose, and the net change is zero.

In a zero-sum game, a player never benefits from communicating her strategy to her opponent. This isn’t how most of life works. For example, giving everyone equal rights doesn’t mean that each person has fewer rights. In this respect, life is not a seesaw where if one person goes up the other goes down, both can be at the same level off the ground.

Naturally, there are situations where zero-sum games are quintessential, such as sports or sharing a dessert. In sports, someone has to win and someone has to lose, and as we’re all aware, for your partner to have a slice of cake, it means one less slice for us to enjoy. On the contrary, buying or selling something is not an example since both parties gain from the situation. One side makes money while the other gets whatever they paid for.

There’s a fallacy in economics called the lump of labor fallacy, in which the general idea is that there is a fixed amount of wealth in the world or a fixed amount of work to be done in an economy. I feel like this is related to zero-sum because it follows the same pattern of thought that something is limited when in reality it isn’t. There probably isn’t an infinite amount of work to be done in an economy, but there definitely isn’t too little.

We need to go deeper

Why do we have a tendency to think this way? It appears there are both immediate and evolutionary causes for us to fall into the trap, and they aren’t always apparent to us, so we need to dig a little deeper.

For an immediate cause, we can point to a person’s individual development, their experience they have with resource allocation, and their worldview. We can speculate that if one had to protect their food from their ravenous siblings or else there wouldn’t be enough for them to eat while they were growing up, maybe they’re more likely to view situations as zero-sum when they aren’t. People growing up on opposite sides of the socioeconomic spectrum may both be more likely to go down this line of thinking, that when one side gains something it means the other has to lose it. Regardless of the factual situations where the rich take from the poor, this is just an example to illustrate possible susceptibility to think in a zero-sum manner.

From an evolution perspective, we can look to our Neolithic ancestors, where there was fierce competition for scarce resources. The development of technology was slow, unlike today, and there was no incentive for humans to understand economic growth. That became the default way we think, which then has to be unlearned. We feel entitled to a certain share of a resource, and today this turns into unnecessary competition between us on things that we don’t need to compete for.

I also don’t want to blame social media, but truthfully, I believe it does play a large role when it comes to our tendency for zero-sum thinking. If you remove the negative stimuli from your life, then it becomes more difficult to experience the negative thought patterns that it helps to cause. On the other hand, social media can be amazingly helpful in finding like-minded individuals, learning, and inspiration.

At the end of the day, like most things, responsible social media use is a balancing act. Some of us are naturally “always online” and have no problem spending much of our free time on social media, some even make their living from social media. For those of us with a tendency to slip into some bad habits when we spend too much time on social media, maybe it’s worth looking into a more balanced social media diet.

It’s all relative

Going down the path of zero-sum thinking can be a relativity trap. We’re frequently looking to others to see their progress in a game that’s unwinnable. We’re playing games of chicken, which is to say, a lot of work trying to pinpoint someone else’s journey when we should focus on our own. We tend to anchor ourselves on the wrong things, like money, Instagram likes, or follower counts. These things aren’t inherently bad to worry about, but it’s when we seethe with envy over another’s circumstances that we only hurt ourselves in the process.

How can we avoid this biased way of thinking? One answer is simply to focus on the value of the things we do own rather than the things we don’t. We can avoid anchoring ourselves on one small part of a much larger picture. If we help others more often, rather than seeing them as competition that needs to be beaten, we can create feelings of reciprocity, which leads to much more fruitful and pleasurable outcomes. Avoiding the short-term gains in true zero-sum situations in exchange for long-term ones is also a helpful reframing.

Personally, I‘m certainly not all aboard the train that is free from zero-sum thinking, especially when it comes to my work or other interests, but if I’ve learned anything from this last year, it’s that we can all do with a bit more self-acceptance and support towards one another. If I can stop seeing situations as zero-sum so often, I will most likely be less envious and happier with my own lot.

Someone else being good at something doesn’t mean I’m unable to reach that level if I too put in the hard work, so I should be inspired rather than defeated. That’s the mindset I’m hoping to cultivate going forward, and I imagine we all could do with a little more appreciation and a little less unnecessary competition.

—

Further reading: